When a new definition of comics is introduced, comic academics and scholars’ debate weather that or any previous definitions actually covers all the aspects needed to constitute a proper definition. Starting with Aaron Meskin’s paper, Defining Comics? [Meskin.2007], these definitions cross over frequently and find themselves in competition.

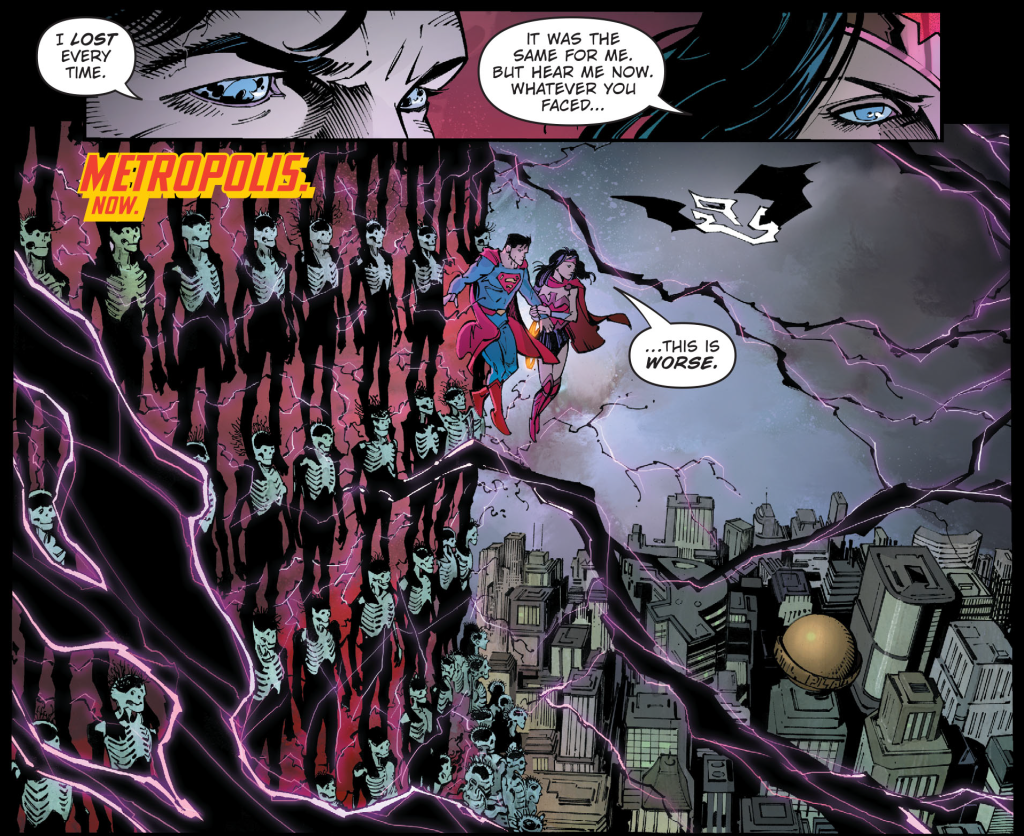

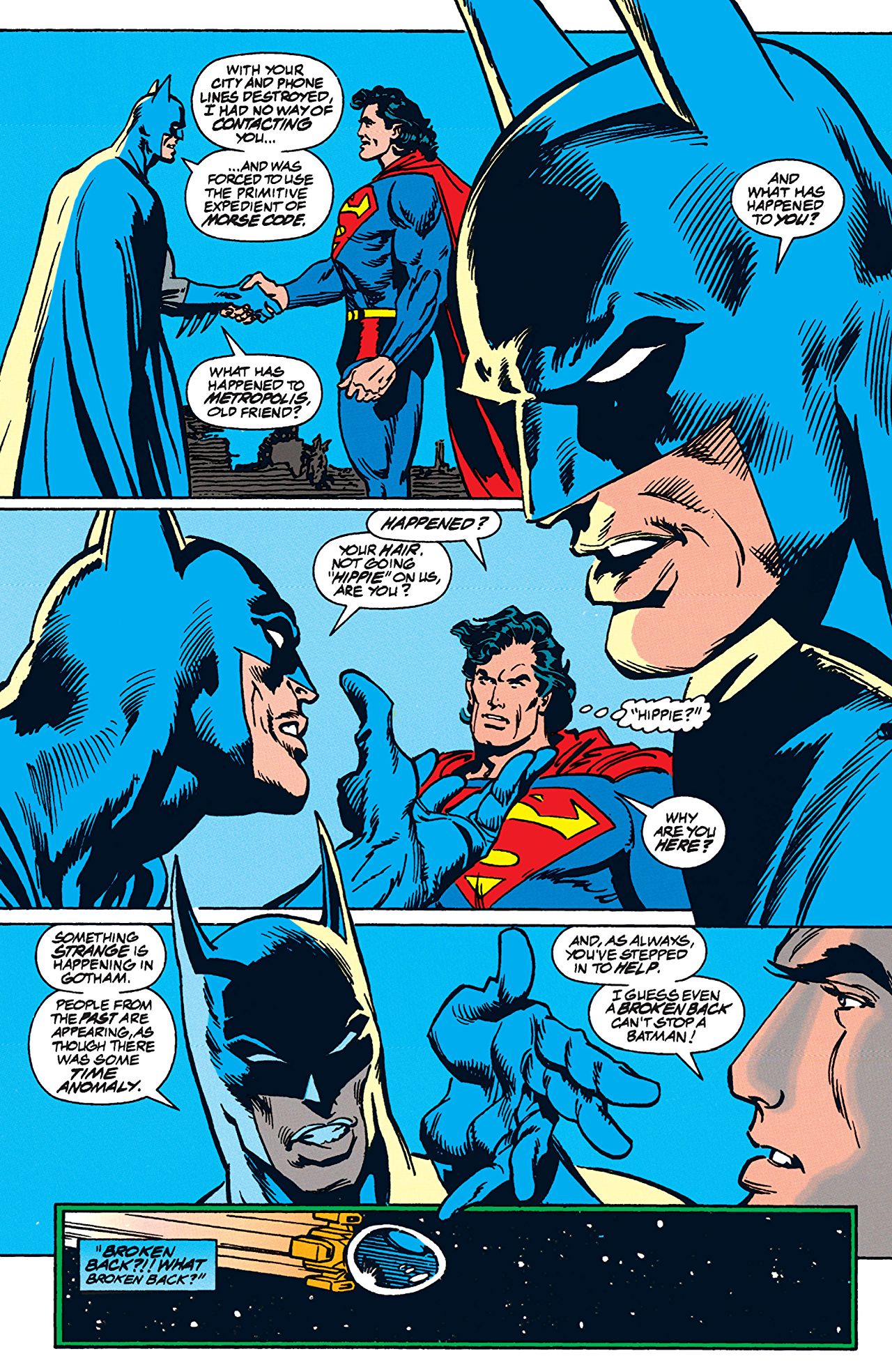

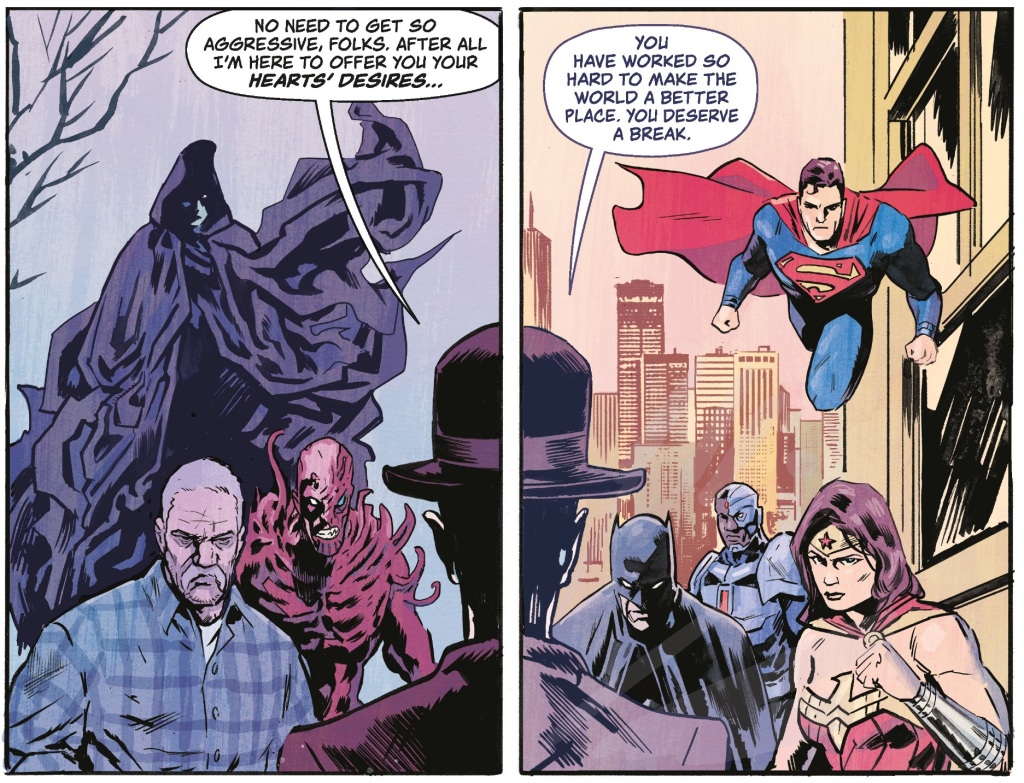

Meskin begins by discussing the work of Hayman and Pratt, noting that they “attempt to provide a traditional real definition of comics in terms of independently necessary and jointly sufficient conditions for the correct application of the concept comic” [Meskin.2007:01]. However, it’s unclear what he means by “traditional real definition”. This feels like a contradiction and implies that there are false definitions. This could be a reflection on how theorists have come to view the definitions proposed by both Will Eisner and Scott McCloud. The work Meskin is referring to for Hayman and Pratt is What is a Comic?, in which Pratt and Hayman state that “x is a comic if and only if x is a sequence of discrete, juxtaposed pictures that comprise a narrative, either in their own right or when combined with text” [Pratt.2011:369]. This statement suggest that comics must consists of pictures in a sequence. Something that writers such as Roy Cook takes issue with when discussing Batman #663 in his paper Do Comics Require Pictures? Or Why Batman #663 is a Comic [Cook.2011]. Going back to Meskin’s description of “traditional real definition”, it seems that the idea of a comic absolutely needing sequential images is the ‘traditional real’ definition that he was referring to. Something that Meskin further notes when discussing the work of Kunzle.

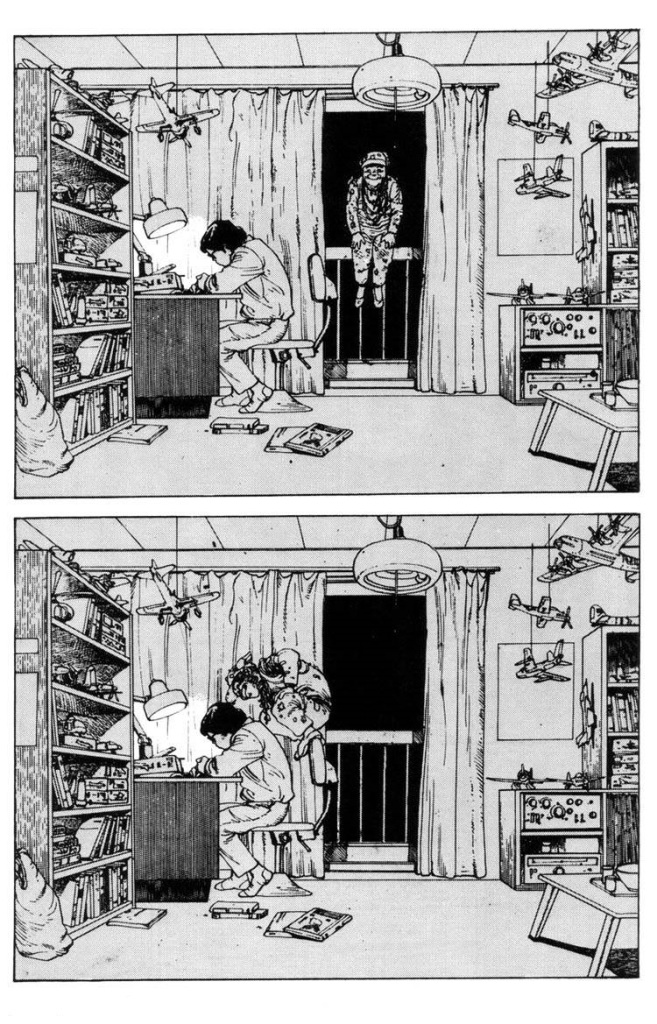

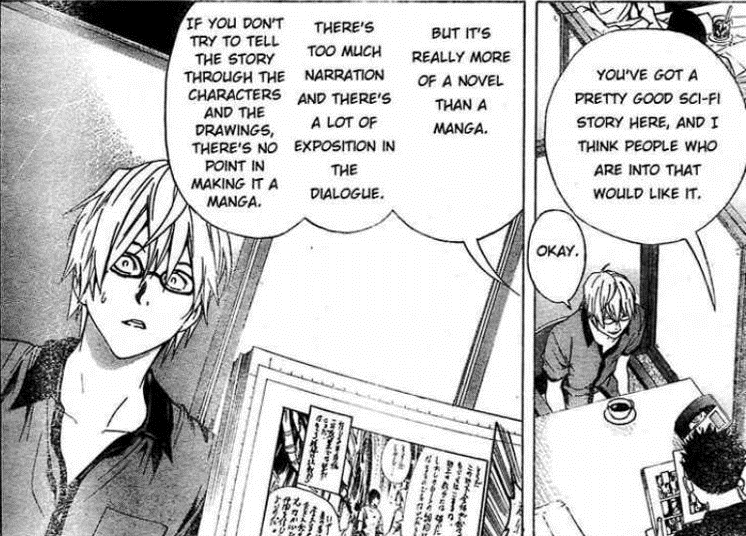

The previous note mentions the place of images as being deeply important to the definition of comics. While Meskin also notes that Kunzle seems to place the morality and topical nature of story above all else, he also discusses the importance of images. “Kunzle characterizes [the images dominance] in terms of what ‘carries the burden of the narrative’ and what is ‘primary’. What does ‘carrying the burden of the narrative’ amount to?” [Meskin.2007:01]. Meskin goes on to add that “perhaps the idea is that audience comprehension of the narrative depends primarily on a grasp of the sequence of images rather than the text” [Meskin.2007:01]. This does heavily imply that images are what should be focused on within comic book theory. However, this disregards the role of the writer and the choice of dialogue within a story. While not based in theory, this argument is made clear early in Ohba and Obata’s Bakuman [Ohba & Obata.2008 – 2012]series. During their first meeting with an editor, Mashiro, a fledgling artist, and Takagi, a new comic writer, receive feedback on their first submission. “Overall, I think this is a well written piece of science fiction, and people who like those kinds of stories would be attracted to it. But this is too much like a novel rather than a manga. There are too many narratives, and the conversations are too explanatory. It’s meaningless to do this in manga form unless you’re able to unfold the story using the art and characters” [Ohba & Obata.2010:016]. While, yes, the editor Hattori is talking about the importance of images, he’s still encouraging the importance of text and writing within comics and manga. The two must be in sync and equally important.

While still on the subject of Kunzle, Meskin begins to bring in the works of both Eisner and McCloud early definitions of comics. Eisner having written about the subject in 1985, with McCloud expanding upon it in 1993. “Comics are, in Eisner’s words, ‘sequential art’, by which he means to pick out a distinctive ‘form of art, or method of expression’. But although dropping the medium and narrative condition might seem attractive given the problems with Kunzle’s account, Eisner’s ‘definition’ if it is really intended to be one, is too thin” [Meskin.2007:02]. This implies that Eisner’s definition, while yes outdated, can’t be fleshed out. Kunzle’s definition states that, according to Meskin “’a sequence of separate images’ with a ‘preponderance of image over text’ that appear (and was originally intended to appear) in ‘a mass medium’ and tells ‘a story which is both moral and topical.’” [Meskin.2007:01]. This definition in fact outdates Eisner’s notes, and implies that the content of a comic is as, if not, more important when it comes to defining it. This means that by Kunzle’s definition, a comic can only tell specific types of stories. Drastically limiting what a comic can be.

Meskin also addresses McCloud’s Understanding Comics [McCloud.1993], criticising his attempt to define the medium. “We shall see that the ahistoricism of McCloud’s account leads it to count far too many things as comics” [Meskin.2007:02]. What Meskin fails to take into account here is that during Understanding Comics, McCloud uses the loose definition Eisner provides and extends it to proves its flaws. He doesn’t reach a full conclusion when it comes to a definition. Instead, he sidesteps the issue by carrying on with Eisner’s notion of simply referring to comics as ‘Sequential Art’ [McCloud.1993:008] [McCloud.1993:009].

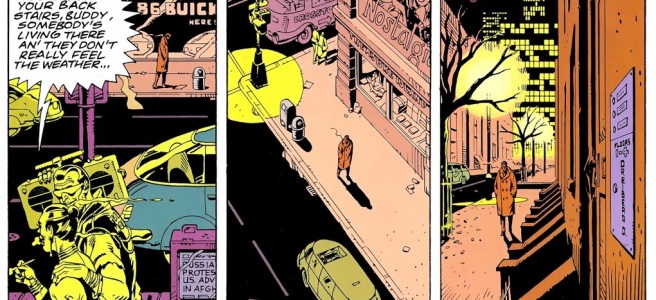

McCloud does discuss the similarities between comics and film strips, “The basic difference is that animation is sequential in time but not spatially juxtaposed as comics are. Each successive frame of a movie is projected on exactly the same space – the screen – while each frame of comics must occupy a different space. Space does for comics what time does for film! However, you might say that before it’s projected, film is just a very, very, very, very, slow comic!” [McCloud.1993:07-08]. McCloud bringing in time is interesting as it is something other definitions seem to neglect. When you apply time to a definition for comics, you are thinking about it the same way as sequential imagery. Comics have the ability to tell a story out of order, the ability to move back and forth between panels is not only a travel sequentially through images but through time. The pages of a comic, either in single issues or in a collected format, exist simultaneously. “A definition that relies on it’s connection to the [time] sidesteps the ongoing debate on image style vs photography, and whether or not the medium must include text or not. It allows for various genres, art styles and the use of both fiction or non-fiction that previous definitions have struggled to overcome” [Laird.2019].The definition including time also helps to distinguish how comics tell a story from how film, novels, or video games.

Previous definitions as well as developing a definition that includes what comics do that other mediums can’t is essential for moving forward in comics academia.

Bibliography:

- Cook, R. (2011) Do Comics Require Pictures? Or Why Batman #663 Is a Comic. Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, vol 69, No. 3 pp. 285-296.

- Eisner, W. (1985) Comics and Sequential Art. W.W. Norton & Company: New York.

- Hayman, G & Pratt, H. (2005) What are Comics? Aesthetics: A Reader in Philosophy of the Arts (Second Edition) pp. 419-424. Routledge: New York.

- Kunzle, D. (1973) The Early Comic Strip: Narrative Strips and Pictures in the Wuropean Broadsheet from c. 1450 to 1825. University of California Press: Berkley.

- Laird, M. (2019) Comics as an Expression of 4th Dimensional Storytelling – A New Definition in Progress. [Online] Available from: https://mikaylajlaird.wordpress.com/2019/12/26/comics-as-an-expression-of-4th-dimensional-storytelling-a-new-definition-in-progress/ [Last Accessed: 29.02.2020]

- Laird, M. (2019) Relativity of Time to Page Count – Comics as Expression of 4th Dimensional Storytelling. [Online] Available from: https://mikaylajlaird.wordpress.com/2019/12/30/relativity-of-time-to-page-count-comics-as-expression-of-4th-dimensional-storytelling/ {last accessed: 29.02.2020]

- McCloud, S. (1993) Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art. Harper Perennial: New York.

- Meskin, A. (2007) Defining Comics? The Journal of Aesthetic and Art Criticism. 65:4 Fall, 2007. Pp 369-379.

- Morrison, G. & Van Fleet, J. (2007) Batman #663: The Clown at Midnight. DC Comics: Burbank.

- Ohba, T. & Obata, T. (2008 – 2012) Bakuman. Shueisha: Tokyo.

- Ohba, T. & Obata, T. (2010) Bakuman Vol. 2: Chocolate & Akamru. Shueisha: Tokyo.

- Pratt, H. (2011) Relating Comics, Cartoons, and Animation. Aesthetics: A Reader in Philosophy of the Arts (Third Edition). Pp 369-372. Routledge: New York.